Part 1: Being a Stranger

I am a stranger in Glarnerland, and this strangeness sharpens the senses, the air smells different. When I look and listen, traverse this unfamiliar place that I have chosen to live in, so rich in possibilities for inspiration and contemplation, a kind of double perspective comes into play between where I was, London, and where I am now. If the past is a foreign country where they do things differently, regardless of whether you stay at home or move away, then we are always entering into an unknowable reality. We cannot go back; it won’t be the same. Nevertheless, the reality of living in another country is more intense; everything is suddenly, not gradually, transformed.

For many strangers in Glarnerland, me included, communication in Swiss German is a personal language-in-progress. We try to wield the High German we have learnt so laboriously in the classroom, only to stumble on the alternative poetic of field, alp and mountain pass that contracts the grammar and extends and bends the sounds and vowels of words. I come from the Black Country in the middle of England where the dialect makes similar moves, impenetrable with its regularised verbs, strange words, higher pitch and musical cadence to speakers of the Queen’s (now King’s) English. It is interesting how the accents of others carry into English – when Swiss Germans speak, the rhythm is more like Welsh than German. Welsh: a language that flows like a brook of compound syllables from the secret valleys beyond Offa’s Dyke.

At the end of the 20th century, I lived in Seville. Here, I first experienced the dreamlike state of an incomplete language, of which Ben Lerner’s novel, Leaving the Atocha Station, offers a redolent depiction: “I almost never spoke,” he says, “although I tried to smile, and to imply with my smile that I understood what was being said around me, letting it fluctuate as though in reaction to their speech,” which led to catastrophic misunderstandings. Describing the bifurcating possibilities for reality when he does speak, finally, and is answered, he captures the confusion of understanding 60%: “She began to say something either about the moon, the effect of the moon on the water, or was using the full moon to excuse Miguel or the evening’s general drama, though the moon wasn’t full… Then she might have described swimming in the lake as a child, or said that lakes reminded her of being a child, or asked me if I’d enjoyed swimming as a child, or said that what she’d said about the moon was childish.” But then he finds a way of listening: “I formed several possible stories out of her speech, formed them at once, so it was less like I failed to understand than that I understood in chords, understood in a plurality of worlds. […] This ability to dwell among possible referents, to let them interfere and separate like waves, to abandon the law of excluded middle while listening to Spanish.” This understanding in chords, through condensed association and image, is tiring and perplexing but also magical and by slowing time down, creatively productive.

Roman Wall and St. Giles Church, remnants in the Barbican

© diamond geezer (flickr) via Wikimedia Commons

The distance between that last then and there and now, for me, lies between Ennenda, an industrial-rural village and its environs in Glarus, and the Barbican estate in the City of London, at the heart of a metropolis of 9 million people. It would seem that living half-way up a 40-storey tower in a bush-hammered concrete utopian dream built on the rubble wastelands of the second World War for 20 years must contrast with living in a Swiss village. Well, yes but on reflection perhaps no, too.

Lake and housing block in the Barbican

© Harry Mitchell via Wikimedia Commons

When we first moved in, friends and acquaintances asked why we had chosen to live in the Barbican with a small child, instead of the family-friendly suburbs. I would reply that, for me, it was like the countryside, with various justifications. Firstly, the ground surface of the Barbican estate, which is often described as an urban village (inhabitants c6,000), is raised above the level of the street and never touches the surface of the clay stratum underlying London. Nevertheless, this wholly artificial ground constitutes a car-free precinct punctuated by sunken gardens, lakes, fountains, and secret passageways, Roman ruins, and medieval fragments. It is a space of safety and freedom for children to roam, rather like the huge garden and fields encompassing my grandmother’s home in rural Gloucestershire. The ancient city streets surrounding the Barbican, whose medieval pattern was kept intact even following the destruction of the Great Fire of 1666 – unlike that of post-conflagration Glarus, periodically host idiosyncratic rituals involving drums, costumes, horses, even occasionally sheep, reminiscent to me now of the Glarner Alpabfahrt (when the cows come down from the mountain pastures).

Looking east from Cromwell Tower in the Barbican © Helen Thomas

Secondly, the Barbican and its surroundings do not constitute a single-species, purely man-made environment: seagulls ride the thermals between the towers of the city; a Peregrine falcon nests on a balcony, rips the meat of its amply provided prey. Herons and ducks live on the lakes, foxes in the carparks. An analogy does not really reside in creaturely co-habitation, however: there are no domesticated animals, no pigs, cows or pets are allowed to live within the Barbican itself, but rather in the available scale of things. It is access to the sublime, or at least the huge – the sky across which weather systems pass from west to east, the ravines between the towers, the line of the distant horizon, even the terrifying sense that the perpetually, rapidly transforming city below is an organic entity beyond human control, which really evokes an out-of-urban perspective.

Part 2: Starting to Walk Through Architecture

The act of reflecting on this condition of Being a Stranger in Ennenda is something I have shared before. In September 2023, my colleague Emilie Appercé at Women Writing Architecture (an independent publishing platform) and I invited six women to my house in the village talk about their experiences of displacement and living in another country. Jaehee Shin is a Korean architect living in Ilanz; Turkish architect Yagmur Kültür in Aarau; Swiss-Nigerian architect Solange Mbanefo in Bern; the work of Zurich-based novelist, poet and performer Melinda Nadj Abonji draws from her childhood experience as an immigrant to Switzerland, while architects Bahraini-German Reem Almannai and Slovak-British Natália Petkova live in Munich and Paris respectively. A surprising revelation for us, after hours of presentations, discussion and visits to the Anna Göldi Museum and the Glarner Wirtschaftsarchiv in Schwanden, was that belonging and the outcomes of desiring it, initially assumed as the ideal for any stranger, became problematic to us as a goal.

These discussions inspired and initiated several projects within Women Writing Architecture, one of them being Walking Through Architecture, which will become a series of walks that introduce different perspectives on the architecture of Glarus. We begin by looking through the eyes of a ‘stranger in the village’, a person from outside who sees and understands the landscapes of Glarus, its buildings and the ways that they are organised, as new and unusual, as not-urban architecture. This is, perhaps, a different way of seeing to those who were born in Glarus, or have lived there continually, to whom these places seem always to have existed and so are barely there and rarely questioned.

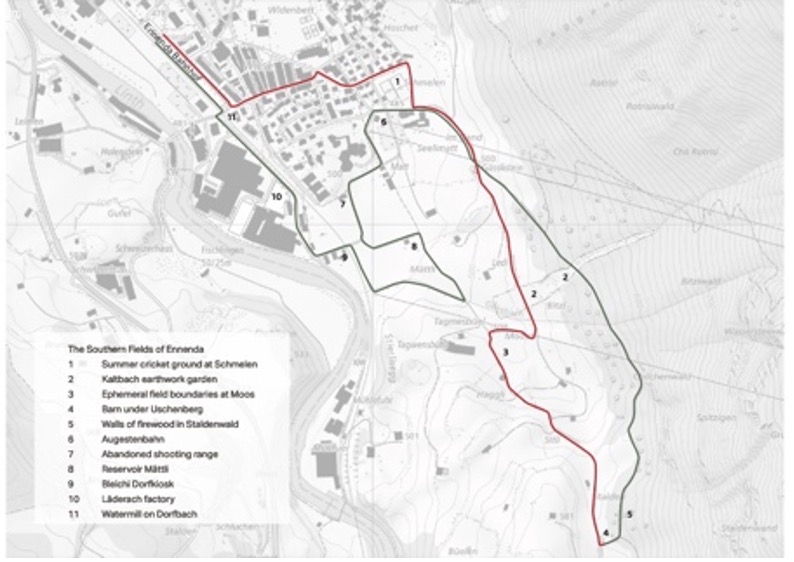

An early example of Walking Through Architecture © Helen Thomas.

This approach to the architecture of Glarus seeks to frame its constructed landscapes – whether industrial complex or intervention, managed water course, hamlet, mountain shelf, alp or slope, valley floor, agricultural mediation, suburb or small town – and their built expressions on their own terms, and not as provincial counterparts to the high architecture of and produced by the city. Walking through Architecture looks for connections between human-made, physical interventions onto and into the landscape, some permanent, some ephemeral, made in service of the human habitat in this place. It considers the influence of topography and the socio-political qualities of the landscape as manifest in human structures over time. So far, selected sites include agricultural structures, permanent and transitory, corrections and collective spaces, dwellings, and places of extraction – as I walked paths through and around Ennenda as a stranger, several sites and locations presented themselves to me as being both architectural and inscrutable, following is one that I found most fascinating.

Photo of Kaltbach enclosure © Helen Thomas.

Even standing at the train station in Ennenda – ennônt aha in Old High German – you are beyond, over the river Linth from Glarus, capital of the canton. Walking east out of the village, where the Platten quarter becomes Schmelen at the Aeugstenbahn cable car station, you find yourself on the Ledi country road going south. Traversing the Seelimatt meadow leads to the Gässlistein, a name reflecting its ancient task of marking and obstructing paths and mule tracks along the Linth dale. This huge red Verrucano stone boulder on the eastern flank of the valley is one of many that strew its steep slopes. At Gässlistein, the road forks and you take the lower way, which continues as Uschenrietstrasse through the Ledi meadow towards Uschenriet.

It is on this stretch of road that you pass through a gap in a grassy berm that bounds a place subtly distinct within the surrounding fields. This boundary encloses on three sides: two almost parallel long ridges rise in the forest of Chilchewald and follow the slope down, broken where the road passes through. When the southern boundary touches the Giessbach ditch beyond, it turns a corner, meeting the northern boundary in a small, enclosed hollow. Looking up to where the trees meet the meadow, a tumble of decorative vegetation amidst a dishevelled muddle of earth and rock produce a picturesque effect. Soon, the road continues into the meadow lands, between Möosli and Bitzi.

Detail of Verbauung des Kaltbachs, Situation/Ausführungsplan

© Landesarchiv Glarus (MAPL 6. 20 2015).

The site plan for the works made in October 1911 reveals something of the technical purpose underlying this would-be walled garden in fine-line detail. While the new then, constructed grass-covered walls, the subjects of the plan, are drawn to plain effect, each stone on the ground is shown. Some have a number, and the complexity of the terrain is delineated by the folds of contour lines enhanced by puffs of earth and shaded ridges, whose roughness suggests that they were fresh when the drawing was made.

On June 15, 1910, there was still a lot of snow in the high mountain regions. While it thawed, the Belingen alp, an elongated hollow formed by a previous landslide on the slopes of Schilt, gathered the melting ice into a temporary lake. As the weight of water increased so did the pressure on the alp’s natural dam until in a catastrophic moment it broke free and cascaded down the course of Kaltbach to the valley below.

Although it was felt that this event would not recur, the new shape of the slope required simple damming measures. Securing the upper reaches was out of the question due to the high costs involved. Instead, it was decided to build a large deposit area from the overflow material at the point where the Kaltbach reaches the meadow at the foot of the steep slope. This has the dual purpose of collecting the debris shown in the drawing and separating it from the water in the event of another landslide. From here, a walled channel leads to the Linth river. The deposit site had a length of 150 metres and an average width of 45 metres.

A conclusion

As I gaze at various drawings and maps of Glarus, seeking clues to understanding the places I encounter and the fields and districts that I walk across, it is the beautiful, mysterious names – the flurnamen – and their abundance that catch my eye. Each one evokes shifting possibilities of meaning and ownership and from there, stories of community and shared experience. These reach back to the times of resistance and independence celebrated, for example, in the Näfelser Fahrt (an annual procession commemorating the Battle of Näfels, 1388, in which Glarus freed itself from the Habsburgs). This is an attractive, romantic notion for an English person coming from a land striated by class relations and held in custodianship, for its fragmented ownership combined with centralised governance belies, even prevents, strategic action.